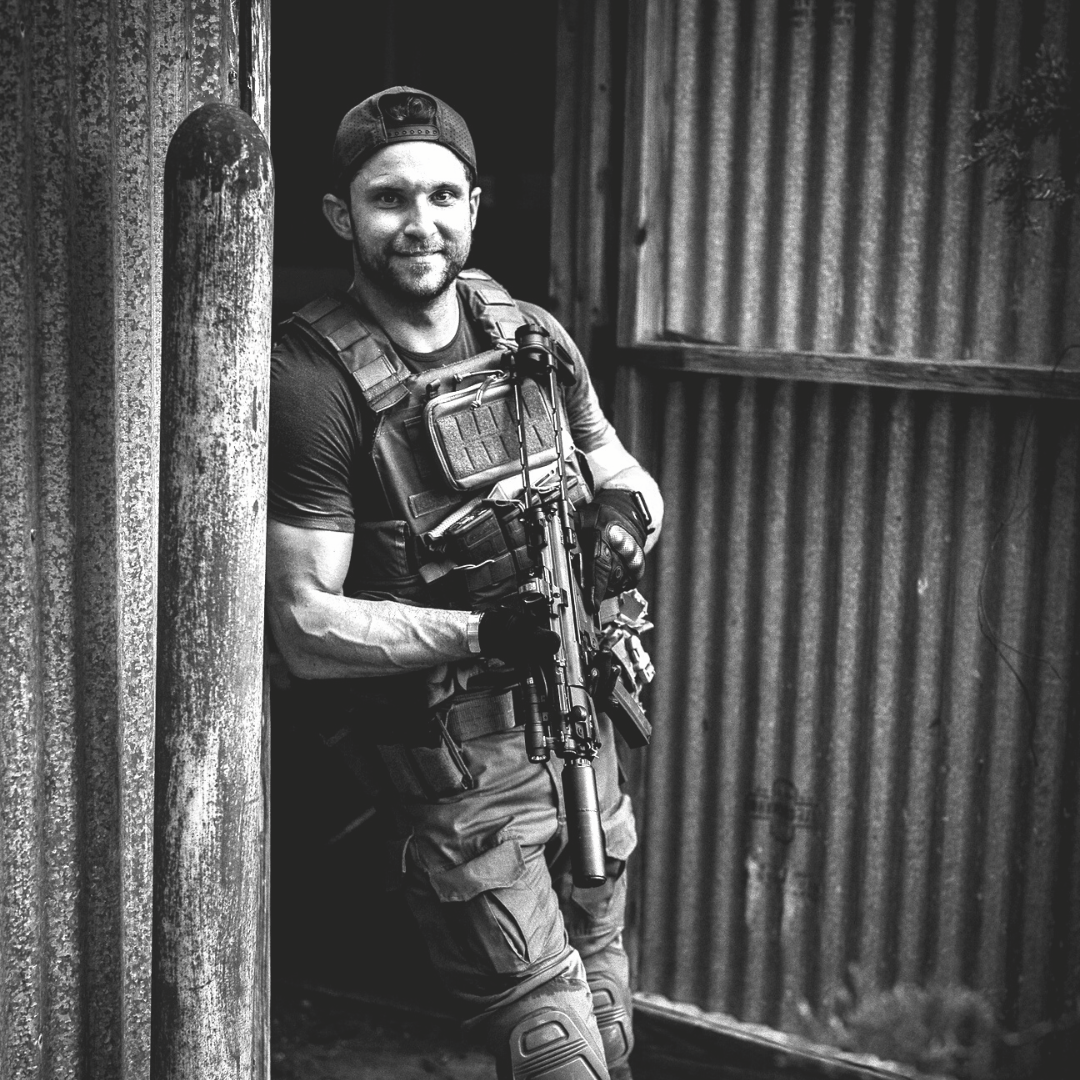

Stories of Honor: David Reid

September 19, 2023

An Army Ranger who was wounded in the line of duty, David Reid recalls the mission that cost him his left leg—and nearly his life. This is David, in his own words, on what the experience taught him about his own strength—and that of the human spirit.

The night that I got injured, we were going after an improvised explosive device (IED) facilitator. This is someone who's making bombs to blow up our troops. We went to Panjaway Province, Kandahar with two 47's full of Rangers. We hit this objective having been briefed that it's rigged. There are explosives in the area and this guy's obviously known for it, so we were told ‘be vigilant’. We did wire reflective training with our lasers; clearing doors, or narrow passageways and you'd get a spider-web-like effect on any thin filaments suspended in the air anywhere from ½ an inch to 7 feet. They would typically rig them at your chest level so that the children could run through and the adults would have to remember to duck. So we land and immediately upon touchdown we hear this huge bang go off and I'm like, ‘What?!’ I honestly thought that someone had negligently discharged (ND’d) their 240-B. It turns out that it was the landing zone (LZ) that had been rigged with these sticks with wires and grenades attached to them. So we landed on an IED immediately triggering it. They had clearly set a little helicopter trap and then it was just all out war from there. We exited in the back, secured the positions like normal. To my immediate right was this cornfield that seemed very odd, and I saw these tracer rounds going through it. We call in air support immediately and they're just bombarding these guys' areas with our air support, which was a C-130 and Apaches. It was a glorious show of force but still they were giving it to us. My objective was to secure the compound immediately to our 6 o’clock from the bird and get our Rangers in to establish a dominant position so that we could react to contact.

We carry in a few 10 foot ladders, and have two Rangers set them up on this compound wall. All these compounds in Afghanistan have 8 to 10 foot walls so we start putting my squad and the Afghanis over and we get into this compound. It was massive. I can't remember seeing it, but it probably had a hundred rooms in it. Think Beverly Hills in Afghanistan. So my guys are reacting to contact with concealment but not much cover. While clearing this, we’re worried that we're going to step on something. This made the situation much more tense as I'm pushing these Afghani Commandos into rooms to clear it and they're hesitating because they're terrified. So I literally have to kick these guys into doors to get everybody dispersed into the proper areas. Then I begin clearing rooms by myself. It's very dark, but I manage to see that there's an alleyway on the other side. There's a room like this 30 foot long alleyway and a wall with a door there. So I go in and clear this alleyway then come back out and clear a couple more rooms. We got a command called ‘Back Clear’ which is to ‘double check’ or check a little bit more vigilantly; so if there's a rug on the wall you're looking behind it. You're making sure that it's very secure and no one's hidden. So I go to ‘Back Clear’ this alleyway and notice there's a door there. Thinking to myself, ‘I want to get our guys in here'’ so I went back, stepping on an IED immediately. There was a pressure plate that was buried in the ground that I had stepped over two or three times.

I remember looking down, stepping, and getting blasted in the face by this and did a front flip right into this building. I was conscious of everything and able to recognize what was going on. I stepped down, saw this flash and just felt this peppering and, before I knew it, I was on the ground. I was just laying there on my back and my night observation devices (NOD’s) were completely destroyed; they blasted off my helmet and I knew my legs were in trouble for sure. I remember thinking I was just terrified to move because of the secondary IED’s. If I move there's obviously explosives in here and I'm gonna roll onto one or something like that. On top of that, in your ear you hear everything else your team is going through over comms. ‘Landslide’ is called, which is NOT what you want to hear and indicates to everyone that the place is rigged and needs to be evacuated immediately. I remember looking up through the doorway into the main compound and just seeing every Ranger I know run right by. That was the single most terrifying moment of my entire life. I felt like I was completely alone in Afghanistan, and it was terrifying to move. ‘I'm alone in a dangerous country where everything is trying to kill me’, and just knowing that I was screwed up very badly, compounded this feeling. Honestly, the terror kind of overwhelmed the pain at first. There's a million things running through my mind. I can't remember the last time I processed that much information in such a short amount of time. The amount of adrenaline I had running through me… I was thinking about EVERYTHING. I was in a relationship at the time. Thinking, ‘Am I gonna see her?’ ‘Why am I here?’ ‘Everybody's leaving!’ All these kinds of thoughts are happening at the same time, and I had a decision to make… It seemed like a lifetime went by and it had just been a few seconds.

I do have to say as a little disclaimer that when ‘landslide’ is called, many people whom I've told this story to have asked why the other Rangers ran away, saying, “I would never do that.” Yes, you would do that because that is a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) so that the rest of the situation doesn't turn into a mass casualty.

At that point, I was able to calm down a little bit and realize I didn't want to die there, which is when I tried to move. Thinking to myself, ‘If I'm going to hit something, I'm going to hit something. I need to get out of here right now!’ With these remain over-day (ROD) sights, you’re carrying a lot of extra gear. I went to roll over but had my assault pack on and couldn’t move with it. So, I literally jettisoned that thing, grabbed my rifle, and low-crawled out of this room. I crawled till I got back into the main compound which was empty. I remember seeing the moon which was giving me the illumination that I needed. It was just enough to look down on my legs… like ‘Oh, shit’. My foot's essentially hanging off at the time and my right leg was hanging off too with a huge hole in my calf. My whole body felt like it was burning. There's still a wicked firefight going on at the same time. That's why I thought, “I'm in trouble… my guys are getting out and leaving.”

I grab the tourniquet and start putting that on my leg and that's the point when my guys came in, found me, and started dragging me out. We obviously know that the compound is rigged to explode so we're gonna have to exit the way we entered… over the ladder. The way they brought me over that ladder was the most excruciating pain I’ve felt in my life. They pulled me up where my back was dragging against the top and then continued to pull my body over and around so that my legs got hooked on the wall as I was going over. At that point, I blacked out. This excruciating pain is when my near-death experience happened.

Because I’m from California, the best way I could describe it is being on the beach at night, having six shots of Tequila and staying in the weight of the ocean. Thinking, “I'm supposed to be somewhere important,” and “This is not right.” With the ebb and flow of the waves crashing on the shore behind me as I wade just at the break. I couldn't see and I was in this kind of loopy environment. Then I came back to reality right when they were dragging me to the position where they were going to perform Ranger First Responder (RFR) on me. Looking up to see something like that out of a Call of Duty game with the C-130 gunship laying down a heavy dose of devastation, helicopters flying by, Rangers shouting over top of me, and working on my injuries. I look over and under this hayfield, feet away from me, I see an IED. I literally point to it, I don't even get a word out, and my guys start dragging me again around another corner. At this point I'm just thinking, “I'm not gonna make it home. There's no way that we're gonna be able to land a bird in here to pull me out.” At this time, my platoon sergeant is in the process of calling in the Nine Line, and I hear him say “Medevac ETA 47 mike's out!”

That's when I started telling my guys to tell the girl I was in a relationship with, “I love her.” That was a big thing for me. I looked at the PA that happened to be there and asked for him to just knock me out. He's like, ‘Can't knock you out, but I can give you something where you won't remember.’ He gave it to me… and then I woke up in the hospital.

I only remember bits and pieces from then and ultimately it's largely a big blackout point. Even that litter ride to the bird I have no recollection of, though I heard it was brutal. Apparently I was cracking jokes, which is good. People usually get weird when they get a dose of ketamine. They forget that they're completely injured, start laughing and joking like everything's great.

The biggest shock for me was waking up in the hospital bed in Kandahar. I did the whole ‘big reveal’, I like to call it, where I pulled the sheets back and saw one leg was bandaged up to high hell and the other one was just gone. This single moment shattered every thought I had about my future and the direction I would take it. I literally thought my life was over at that moment. I wouldn’t be able to do it or anything anymore, and it broke me a little bit. As a Special Operations war fighter going to someone who couldn't even stand on crutches anymore. I was so messed up, I ended up dropping from 185 lbs. to 130 lbs. in a matter of weeks. I had shrapnel all over, especially around where my goggles were. I woke up to my favorite Sergeant Major from 1st Battalion just sitting there. So I looked up at him wondering why it was him that I was waking up to, and asked, “With all due respect Sergeant Major, what the f*** are you doing here?” He looks at me like, “What are you talking about?” then leads right into, “Well, you know I was just in the area doing some stuff. Is there anything you need; anything I could get you?” I quickly mentioned that I had some of my stuff, but asked if he would go back and get some other items from my hooch. He didn't get a single item that was mine. It looked like he just walked around the whole barracks and just stole everybody's shit. More than likely thinking, “He's going to need this way more than you.”

This is about the time that I had to make the call with quite a few people, parents, friends, and my lady at the time. I had to let them know that I had been injured and would be coming home soon. That was rough for me. There's a lot of background stuff that people don't talk about, even on our shows, especially the briefings that the leadership gives you. Generally like listen, “Say this, this, and this. Don't say this. You have to word it this way or they're going to worry.” All while I’m saying that I don't want to call them and asking if they could make the call for me. They fervently replied, “No, we need you to call them so that they know immediately you’re okay.”

That was a rough journey. In the recovery section, I had 11 surgeries– revisions on my leg alone and going through the wound vacs where it was difficult for me to even take a piss anymore. I had all these hoses coming out of every direction. I had no leg and my other leg was ruined so there was no “getting into it”. It was like getting into a wheelchair to move a foot while having to situate these wound vacs and all the IV bags. It would easily take an hour just to go to the bathroom. I remember the first time the PT came in with a pair of crutches after my leg heals up a little bit and she says, “All right, let's go for a lap”, and I said, “Get the f*** out of here. You want me to do what?” Fortunately, they persisted and came back every single day. Til finally, partially out of annoyance, I told myself to just give it a go.

This journey towards recovery is definitely soul crushing to go from that high impact dude to passing out from simply standing up in my crutches even while supported by a belt. That determination and strength of will that the Army indoctrinated into my mentality benefited me tremendously. I always tell people in their journey to recovery that there's essentially two routes they could go. They could allow their situation to defeat them, or they could use that to bolster themselves up, overcome that obstacle, and become a symbol or a message for others that have faced adversity in their life. It starts with a choice.”

David's story provides a powerful insight into the human condition and reveals several key concepts that are integral to our understanding of what it means to be human. At its core, David's story highlights the true meaning of sacrifice, courage, duty, self-transcendence, resilience, and leadership. These concepts are not just essential to our understanding of David's experience, but they are also crucial to our understanding of the human experience as a whole.

- The concept of sacrifice is deeply ingrained in the human psyche, as it showcases the ability to put oneself second in the service of others. It reveals the nobility of the human condition and the true essence of altruism, which is an incredibly powerful force for good in the world. In David’s case, his selfless actions and willingness to risk his own life to prevent harm to others, highlights the importance of serving something greater than oneself.

- Courage is another hallmark of the human condition, as it reveals the depths of human fortitude and bravery in the face of extreme danger. This concept is readily apparent in David’s story, as he and his team pushed through fear and uncertainty to accomplish their mission, finding the strength to carry on despite the risks. The fear of death is a natural human instinct, yet David and his fellow Rangers were able to reconcile this fear with their duty to protect others, showcasing the true meaning of bravery.

- The concept of duty is another integral aspect of David’s story, as his sense of responsibility to his country and his fellow Rangers guided his actions. Duty and responsibility are critical components of the human psyche, as they provide a sense of purpose and direction. It is through these roles that most come to view their place in society and the world at large.

- The concept of self-transcendence is also evident in David’s story, as he put the needs of others before his own. The ability to transcend one’s own self-interest and dedicate oneself to a higher purpose is a hallmark of true heroism. David’s experience shaped his sense of self and purpose, highlighting the transformative power of self-transcendence.

- The concept of resilience is also critical in David's story, as he and his fellow Rangers coped with the stress, trauma, and challenges of their chosen profession. Resilience is the ability to bounce back from adversity and continue to serve, even in the face of extreme hardship. David's ability to push through these challenges is a testament to the human spirit's durability and strength. This concept reveals the importance of perseverance and the ability to overcome adversity.

- Finally, the concept of leadership is clear as his fellow Rangers followed the guidance and inspiration of their leaders. Effective leadership is critical in any high-stress environment, as it provides direction, guidance, and motivation. The ability to inspire and guide others in the face of death is a hallmark of true leadership, highlighting the importance of this concept in any field of work.

The more we learn about David’s story, the more apparent these concepts of the human condition become - sacrifice, courage, duty, self-transcendence, resilience, and leadership. Despite facing numerous challenges and setbacks, David was able to overcome them and emerge stronger and more resilient. This ability to bounce back from adversity is an important aspect of the human condition, as we all face challenges in our lives and must find ways to cope with them. David’s ability to adapt and overcome adversity in the face of immeasurable odds followed by constant challenges and setbacks is not just admirable, but a testament to the capability of the human species.

Through his experiences, he was able to learn more about himself, his strengths and weaknesses, and what is truly important in life. This journey of self-discovery is a fundamental part of the human condition, as we are constantly growing and changing as individuals. Despite facing difficult circumstances, David never gave up hope and continued to strive for a better future. This ability to maintain hope and optimism is a crucial aspect as it helps us to persevere through difficult times and ultimately achieve our goals. In the end, the only constant is change, and the faster we accept that, the more we can introduce hope and optimism in the face of future adversity.

Also in Ascend Together Initiative

Memorial Valor Foundation

April 25, 2025

Memorial Valor Foundation's mission is clear and unwavering—to remember, honor, and memorialize fallen Special Operators by providing support to their Gold Star families, and the SOF families whose loved one is no longer with us. They achieve this through annual flagship events like the Memorial 3-Gun Competition, along with newly introduced galas, golf tournaments, and skeet shoots. Each event uniquely commemorates heroes by sharing their stories, celebrating their legacies, and providing vital support to their families.

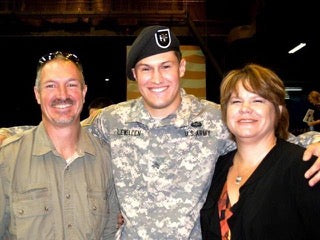

Stories of Honor: Matthew Lewellen

December 31, 2024

We live life dialed to eleven.

Get discounts, stories, and more from Terra Arma delivered to your inbox.